1883 Colonial Exposition, Amsterdam

1883 Colonial Exposition, Amsterdam

Card Game

By Holly Griffin

This text is freely available for the purpose of academic teaching and research provided the text is distributed with the header information provided.

Download EssayEssay on a card game from the 1883 Colonial Exposition, Amsterdam created as a final assignment in World's Fairs: Social and Architectural History , HONR 219F, Spring 2001

Titles of texts, foreign words, and emphasized text have been encoded

Keywords:

- Internationale Koloniale en Untvoerhandel Tentoonstellung (1883: Amsterdam)

- Exhibitions

- Exhibition buildings

- Souvenirs (Keepsakes)

- Playing cards

- Essay

- Board Games

- 1901-2000

- Europe

- Holland

- Amsterdam

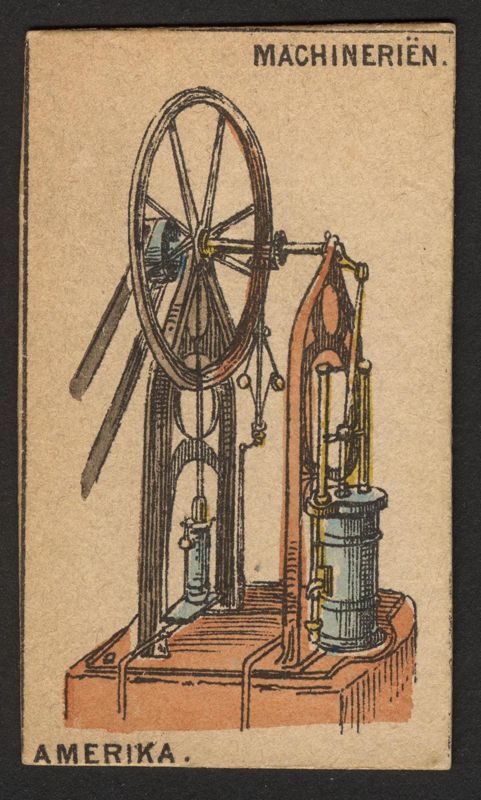

The card pictured here is one of a larger deck, comprising a round-style game. Card games were a popular souvenir item among fairgoers. The game was a competition between nations illustrated in the larger cards of the set, measuring 4' 1/2;" by 2'3/4", representing the countries holding colonies at the time, and the smaller cards, 3" by 1 3/4", representing major industries. Represented were the Netherlands, listed as the first country on the direction sheet, England, Germany, Belgium, France, Russia, the United States of America, Turkey, Italy and Spain.

There were twelve cards for each of the ten industries, including a sheriff, a cannon, a vehicle, furniture, poultry, machinery, velocipedes, agriculture implements, musical instruments, and children's toys. For the same industry, each card features the name of a different colonizing nation. The colonial policies followed by the Netherlands in the 1880s coincide with the overall theme of the card game. Just as Netherlands played the role of a colonizer in the real world, the card game of its Amsterdam fair represented the colonization process of inferior countries to the superior nation. A victory in the game was obtained in a way similar to the method by which a colonizing nation would gain its colonies.

Printed in black on a white background, the cards have been hand-painted with watercolor ink. One can determine that they were not created using a stamp, as strokes are visible. The American colonization card displays several typical industries and technologies found in United States, including a flag, a picture representing the mining industry, a telegraph, a sewing machine, a factory, a watch, and what is surmised to be a white male industrialist with a top hat.

This card game represents an industrial competition, the winner earning the greatest quantity of industry cards. On the front cover of the box holding the cards, there is a picture of the central underpass which served as the main entrance to the fair. The entrance, built in a Moorish style, was reached by passing through the Rijksmuseum gate. This museum is still in existence, and is the largest installation of its kind for art and history in the Netherlands. It is perhaps best known for its collection of 17th-century Dutch masters, with twenty paintings by Rembrandt and many priceless works by Vermeer, Frans Hals and Jan Steen Rijks.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Netherlands experienced little economic growth. By the 1860's, however, this trend began to reverse, partially due to the opening of the Noord Canal, which brought oceangoing vessels to Amsterdam. At the same time, the national rail system improved rapidly, and a new central station opened Amsterdam in 1879 (Findling 78). International expositions promoted economic growth and tourism; as Amsterdam shove to emulate the cosmopolitan flavor of cities like Paris and London, a world's fair would be an asset to the city (Mattie 60).

A French entrepreneur, Edouard Agostini, saw potential in a fair in the Netherlands, and mailed brochures to influential Amsterdam business leaders (Mattie, 60). According to Mattie, "because the Netherlands was not well known except of the wealth of its colonial empire, the committee decided to organize the fair as a colonial exhibition, giving it the formal name of Internationale Koloniale en Untvoerhandel Tentoonstellung te Amsterdam" (Mattie, 60). Although the idea of a fair was met with some skepticism, planning continued.

The Dutch government initially refused to pledge any money for the event; however a persistent Agostini eventually found backing in a little-known Belgian financial firm, Tasson and Washer. The firm was prepared to construct the main building in exchange for all of the entrance fees and proceeds from leasing exhibition space. The Dutch became suspicious and resentful because mainly French and Belgian architects were responsible for the fair's construction. Fears were realized after the closing of the fair when Tasson and Washer went bankrupt, despite the exhibition's high returns, and independent investors received a return of only one fifth of their investments (Mattie, 60).

Despite financial setbacks, the Amsterdam exhibition, the first international exposition with a colonial theme, marked its place in the history of the world's fairs. Entire native dwellings from overseas were erected, and were inhabited by indigenous peoples, treating fairgoers to an encounter with the exotic. In subsequent fairs, native villages complete with "savages" became fixtures, demonstrating the superiority of Western culture. Additionally, the fair was unique in that it emphasized the trade of industrial products as opposed to their manufacture (Mattie, 60).

An area of wasteland on the south side of Amsterdam was selected, as it offered adequate space for the fair. The rectangular main building measured 1,000 by 394 feet, and was built over a canal. In addition to the Main Building was the Dutch Colonial Building, measuring 417 by 250 feet. Inside the Colonial Pavilion were several different types of agricultural products, cultural treasures, native arms and more. Although the Main Building of the Antwerp fair was acceptable to critics, the Colonial Pavilion was not. Critics attacked both the appropriateness of the building as well as the purity of its style (Mattie, 62). The Colonial Pavilion, (which was also partially built over water) and the Machinery Gallery enclosed a triangular space for smaller pavilions, including one for the city of Paris. In front of the Colonial Pavilion was a small settlement representing various oversees colonies.

Although only the Netherlands and Belgium had comprehensive exhibits, foreign participants included most of the other countries of Europe, as well as China, Japan, India, Turkey, the Middle East and Africa, the United States and Canada among others (Findling 78-79). The remainder of the site served as an amusement park (Mattie, 61). At the focal point of the amusement park was the Music Pavilion, which was surrounded by German, Dutch and English restaurants (Mattie, 61). There were several other buildings on the site, including a pavilion for the city of Amsterdam, a Japanese Bazaar, small shops and restaurants. A canal, traversed by a bridge of bamboo, ran through the fairgrounds, providing a home for a Chinese junk (Findling, 78)

At the time, finding an appropriate architectural style for the Netherlands raised much controversy. Consequently, the exhibition buildings received mixed reviews. At stake was the concept of architectural "truth," based on the question of whether or not the exterior of buildings should reveal their functions, and whether those exteriors should be stylistically pure, regardless of the chosen style. For at least one group of Dutch architects, "honest" architecture was epitomized by the Rijksmuseum, designed by P. J. H. Cuypers (1827-1921) (Mattie, 62). Cuypers was responsible for the design of many churches in neo-Gothic style in the Netherlands, and as such was one of the leading figures in the process of Catholic emancipation in the second half of the 19th century.

Cuypers was also responsible for numerous restorations of existing churches, including those of many medieval, now protestant churches. His attempts to restore parts of such churches was an occasional a source of conflict within the protestant community. Apart from his architectural work, Cuypers was a gifted artist in other respects, his work including several monuments and tapestries. Despite his many accomplishments, Cuypers is usually remembered today as the architect of the central station and Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Many of Cuypers' more important designs have already been demolished or otherwise destroyed, but many still remain (Archimon). The incorporation of the Rijksmuseum into the Amsterdam exhibition considerably enhanced its allure(Mattie, 62).

Unfortunately, very few designs were met with general approval. One that did, however, was the fa??ade of the Main Building, designed by French architect Paul Fouquiau. A temporary structure, it was built of wood, with a glass roof, but it was covered with plaster and painted canvas to give the impression of marble. The fa??ade was a 164 foot-wide wall made of canvas, wood and plaster with two 82-foot high towers at each end. The huge, drooping piece of canvas was suspended between the two towers and was decorated in a grotesque Indian motif, featuring large elephant heads and other animals, all cast in plaster. The building's other decorated motifs also evoked colonial outposts, and in this sense the exterior was consistent with the interior, a feature of "honest architecture." The interior design was by the Belgian Gedeon Bordiau, who also designed the Main Building at the 1885 Antwerp exhibition. The entire interior exhibition space had an area of nearly 650,000 square feet.

The early seventeenth-century Dutch Renaissance style was chosen for the remainder of the pavilions at the Amsterdam Colonial Exposition. During this period, Dutch provinces developed into a strong nation and freed themselves from the yoke of the Spanish. The Italianate Dutch Royal Pavilion, which was a departure from the national style, was the subject of attacks by critics as well. Foreign pavilions that demonstrated their own national histories, however, generally earned critic approval (Mattie, 62).

Thousands of visitors attended the fair, staying in new hotels like the 'Americain' and 'Krasnapolsky', buying souvenirs from the exposition, and stimulating the economy of the city. When the exposition closed its doors on November 1st, more than one million tickets had been sold (World). The 1883 Colonial Exposition in Amsterdam had indeed been a success.