Paris 1889

Paris 1889

Russian House

By Liz Tymkiw

This text is freely available for the purpose of academic teaching and research provided the text is distributed with the header information provided.

Download EssayEssay on the Russian House from the Exposition universelle de 1889 (Paris, France) created as a final assignment in World's Fairs: Social and Architectural History , HONR 219F, Spring 2006

Titles of texts, foreign words, and emphasized text have been encoded

Keywords:

- Garnier, Charles, 1825-1898

- Paris World's Fair (1889)

- Gallo-Roman House. Paris World's Fair (1889)

- Exhibition buildings -- Design and construction

- Exhibitions

- Racism

- Essay

- 1901-2000

- Europe

- France

- Paris

The 1889 Exposition Universelle, like all other nineteenth century fairs, was mainly concerned with the progress and modernization the "civilized" world had undergone. While many exhibits like the Exposition de l'Economie Sociale and the Galerie des Machines demonstrated new social and economic breakthroughs, others were devoted to the past and to less "developed" cultures. The Street of Cairo exemplified this dichotomy, but a better example was Charles Garnier's Histoire de l'Habitation Humaine. Garnier was a French architect, born in 1825, best known for his design of the Paris Opera House. He was also recognized for his extensive work on the Histoire de l'Habitation Humaine; a subject on which he wrote a book published in 1892, explaining motivation and purpose for the exhibit. According to Nils Muller-Scheessel, who has studied the representation of prehistory at the world's fairs, "Paris 1889 became the international exhibition of prehistoric archaeology" (Muller-Scheessel 2001).

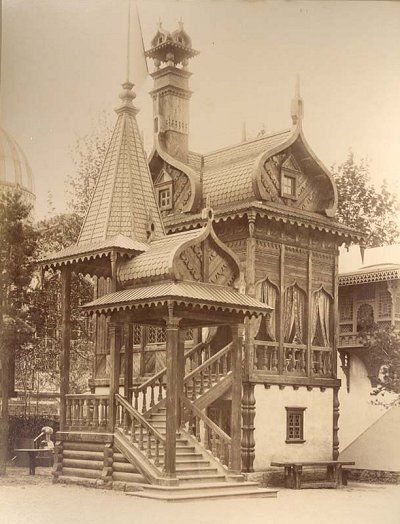

The University of Maryland Architecture Library preserves a bound album of photographs representing many foreign buildings at the 1889 fair, as well as a large sample of Garnier's smaller sized buildings. This seems to be a privately assembeled and owned album, as there is no publisher or copyright date, and all of the pictures are labeled by hand and are credited to different photographers. Unfortunately, there is no name in the book with which we could identify as the collector. The album is organized like the exhibit itself, with the pictures (and hence buildings) grouped by epoch and location. This picture of the Russian house (credited to J.D.) is a black and white photograph, slightly yellowed with age. This exceptional, if not unique, document provides a vivid impression of Garnier's Histoire de l'Habitation Humaine and its underlying symbolism.

The exhibit, which was located next to the Seine River in front of the Eiffel Tower, represented forty-four different cultures on a plot of land 400 meters along the Quai d'Orsay (Muller-Scheessel 2001). It was divided into three categories: "prehistoric", "historic" and "primitive contemporaries" (Garnier 1892). While these designations were rather random, "prehistoric" generally meant extinct cultures, "historic" early stages of existing countries, and "primitive contemporaries" the so called savages, for example island and African cultures.

L'Histoire de l'Habitation Humaine was meant to "record human history for future generations" and to give people a chance to experience the past and other cultures outside of a museum (Jourdain 1892). The other agenda of this exhibit was to show how far humanity had come in technology, morals, and intelligence (Muller-Scheessel 2001). L'Histoire de l'Habitation Humaine was accepted at the time as an appropriate display, but today we can discern much racism and misunderstanding of other cultures. Articles written at the time, and Garnier's explanation itself, show clearly that these buildings represented the negative view developed nations had of cultures different from their own. Western society back then had a superiority complex and thought that less "sophisticated" and technologically advanced cultures needed to be fixed. The Habitation Humaine proclaimed "look how far we've come and look how behind these people still are". The same principle prevailed at the Colonial Exposition of 1931, also located in Paris. Colonialism was the process by which "civilized" nations took over and exploited cultures different from their own.

In 1889, these inherent prejudices of Western society could be seen in the buildings and exhibits themselves. Many of Garnier's habitations were "dramatized" to make them look more primitive or foreign. Some of the colors and decorative details were not entirely accurate. Much of this was intentional, as Garnier almost meant to encapsulate a whole culture in a single building. Another reason was that Garnier???s time and budget were limited (Jourdain 1892).

The Russian house featured was located in the historic section, along with the house for the Huns, the Gallo-Romans, and the Scandinavians (Jourdain 1892). This is appropriate because Russia was invaded by Scandinavian pirates and then by Slavic assailants, around the 9th century, who developed a new culture by entering into contact with the Byzantine Empire, to the south. This mixed heritage is evident in in Russian architecture. Most Russian houses are constructed of wood, as in Scandinavia, and design ideas can be credited to the Slavs. According to Garnier, contact with the Byzantium culture dramatically changed Russian architectural ability, greatly improving on the wood cabins seen previously (Garnier 1892).

Our photograph clearly illuminates Garnier's theories. The building is built mostly of ornately carved wood. There is decorative trim on the eves and the banisters of the railings, as well as beautiful carvings on the outer walls of the house. The house's green and red paint are indicative of Russian culture as they were many of the colors used in Russian folklore and drawings. The roof is the traditional onion dome shape, which was climate-appropriate as it let snow slide of and thus prevented breakage and leakage. The Russian house was built with similar materials to the Slav house, but is more ornate, showing the origins of the architectural style as well as the unique Russian touch (Jourdain 1892).

In his book, L'Habitation Humaine, Garnier goes into detail about why he built the Russian house as he did. The lower level of the building is made of plaster or stucco. This material was appropriate to the climate, as it would often snow a lot and wood could rot. This level was traditionally meant for the man of the family. There was a separate door and several windows on this level, providing the man with a distinct sanctuary as well as private access to the home. The windows in the lower level of Garnier's house featured the star of David, showing how important religion was in their culture. The upper level was for the women and was constructed of wood. It had a separate stairway so the women and children would not have to walk through the men's quarters to get inside. This illustrates the male dominated society of old Russia, as they had just recently adopted monogamy. This part of the house was also more ornate and contained most of the decorative trimmings as well as curtains on the heavily Byzantine-influenced windows, which the bottom level lacks. These curtains were made of the traditional fabrics and patterns of Russia. This part is much more open than the men's quarters reflecting the differences in genders in that culture. The men's part of the house was made of stronger material and was more functional; its only job was to support the house, it didn't need to look pretty. The women's section was more open and decorative with more elegance. The high pointed roofs allowed a small amount of room for a second floor for the servant quarters. The servants weren't given much room, but it was convenient to have them living in the same house (Garnier 1892).

For the grounds surrounding the house, Garnier tried to be true to life. In the photograph, you can see a water pump in the back and benches around front and back reflecting the Russian connection with, and reliance on, nature. The pine trees surrounding the house would have been similar to those found in Russia. You can also see a corner of the Arab habitation in the background, showing how all the Habitation Humaine buildings were packed fairly close together so a visitor could see as much of this exhibit as possible.

L'Habitation Humaine was popular and successful. Charles Garnier received a lot of good publicity after the fair, and rightly so. While his covert arrogance is obvious today, at the time, Garnier was credited for creating a series of ancient or foreign cultures accessible to a very large public. Fairgoers experienced designs and architecture that would have remained unknown to them. These cultures were essentially used to glorify the present, and they did a very good job of that. Next to all the primitive and ancient habitations, the Eiffel Tower and other miracles of modern day architecture and society looked even more marvelous than they were.