Bird's-Eye View of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

Bird's-Eye View of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

St. Louis, 1904

By Holly Griffin

This text is freely available for the purpose of academic teaching and research provided the text is distributed with the header information provided.

Download EssayEssay on the bird's eye view of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition: St. Louis, 1904 created as a final assignment in World's Fairs: Social and Architectural History , HONR 219F, Spring 2001

Titles of texts, foreign words, and emphasized text have been encoded

Keywords:

- Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904 : Saint Louis, Mo.)

- Exhibitions

- Essay

- 1901-2000

- North America

- United States

- Missouri

- St. Louis

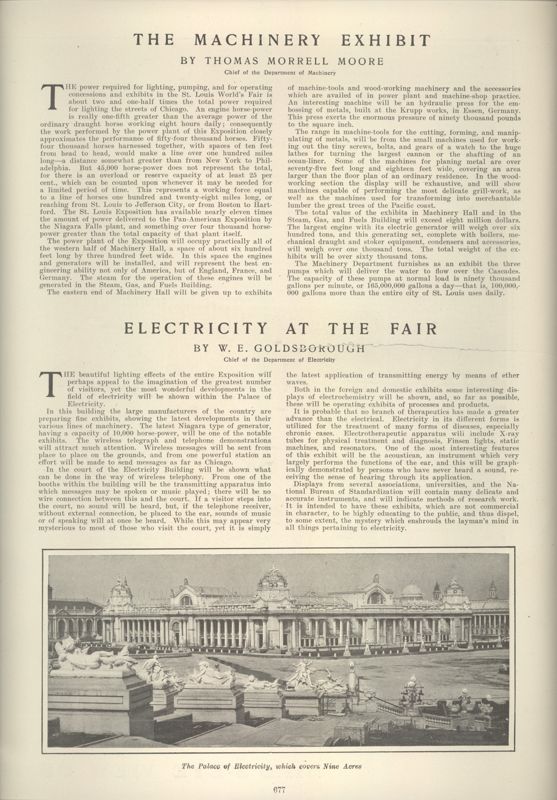

This bird's-eye view provides a basic layout of the Louisiana Purchase International Exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. This periodical illustration was printed on pages 678 and 679 of Harper's Weekly magazine, and was an extracted centerfold, as is evident by staple holes in the center crease. The surrounding pages of the magazine included information on the Palaces of Electricity, Machinery, Transportation and Horticulture. The entire image is approximately 13 5/8" wide and 19 inches long, and includes Festival Hall in the center with its two hemispherical lagoons, and other fair buildings radiating out from it. The illustration gradually fades on the edges, eliminating scenery that would distract the viewer from the fair. It is from a relatively distant vantage point, and thus the architectural details are difficult to discern.

In 1904, St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the United States, and was expanding rapidly. The city had become the "Gateway to the American West." Chicago had recently hosted the giant Columbian Exposition, establishing itself as a location of international import. By hosting a fair St. Louis would maintain its pace with Chicago and make known its presence as an influential city. The fair marked the centennial of the signing of the Louisiana Purchase Agreement between France and the United States, a historic purchase by the United States of land from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains, and from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. The exposition opened a year late, however, in order to accommodate foreign exhibitors and American states (Mattie 118).

The site selected for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was Forest Park, a heavily wooded area often referred to as the "Wilderness" (Mattie 118). The park was at a central point between the north and south of town, away from unsightly factories and slums, but easily accessible by public transportation. A forty-minute carriage ride from downtown St. Louis, the area was not congested (Findling 179). The location was controversial, however, as many citizens objected to the clearing of this area of great scenic beauty (Mattie 118).

Unfortunately, Forest Park was not without its problems. According to Timothy Fox,

the entire site was destitute of water supply, gas, sewers and drains, and its generally rugged broken conditions entailed many engineering difficulties and necessitated a large expenditure of money to establish that uniform, generally level condition necessary for the grouping of the large exhibition palaces.

As many as fifteen-thousand individuals worked daily to convert this park into a suitable location for a fair. A heavily polluted and flood-prone river, the Des P??res, flowed through Forest Park, and was rechanneled and moved underground to facilitate construction (Mattie 118). The city was forced to invest a great deal of money into the water system in order to provide an adequate supply to both the exhibition and its citizens. The construction of the fair eventually extended onto the campus of the unopened Washington University (Mattie 179). Covering 1,272 acres, the completed grounds were so large that physicians warned weaker patients to avoid the fair lest they collapse (Rydell 53).

Opening on April 30, 1904, The Louisiana Purchase Exposition was viewed as an event that might help restore an economy hurt by the depression of the mid-1890's, and an image badly tarnished by a violent transit workers' strike and political corruption in St. Louis. The strike brought to attention the city's poor municipal system, as well as the corrupt practices among business and political leaders. St. Louis residents viewed the fair as an opportunity for a general campaign of urban improvement, constructing new streets and playgrounds, and painting old buildings (Rydell 52).

In order to increase foreign participation, fair representatives traveled to Asia, Latin America, and North Africa with an invitation to bring people and exhibits to St. Louis. David Francis, president of the World's Fair Commission, mobilized the Businessmen's League, and at the initial fundraising rally in 1899, members pledged nearly five million dollars in one evening. Within a year, a city bond and a federal loan subsidy provided ten million dollars to the cause. Eventually the federal government doubled its original contribution when construction proved more costly than initially anticipated (Findling 178).

Clearly apparent in this bird's-eye view of the fair is the fan-like shape, devised by French architect Emmanuel Masqueray (Findling 181). The main exhibition palaces radiated out from the focal point of the fair, Festival Hall. The Hall is the center building in front of the forest on the periodical image, occupying an ideal location atop Art Hill. The fair possessed broad, curved boulevards, spacious plazas with lagoons, sunken gardens and beautiful, shady open spaces. There are no excessively tall buildings present in the bird's-eye view, because a set requirement was that no building could be higher than sixty-five feet above average grade, thus there are no excessively tall buildings in the bird's-eye view (Findling 180). Additionally, all buildings were required to have windows that could be opened and entrances on all sides (Findling 180). The main palaces of the fair featured the Neo-Classical elements and observed rules of composition taught at the Paris Ecole des Beaux Arts, emphasizing symmetry, large-scale planning, and elaborate ornamentation.

Festival Hall, described in an online essay by David Coleman, had a 145-foot diameter dome, and housed a huge concert auditorium. Behind Festival Hall was the Fine Arts building, with its smooth walls and fa??ade of column shafts (Findling 181). This building still exists today as the St. Louis Art Museum. In front of Festival Hall were the Cascades. Colored white in the bird's-eye view and running between the two lagoons, the Cascades were studded waterworks that demonstrated the city's mastery over the natural elements that previously challenged it (Mattie 120). One important aspect of the Cascades was their constant motion, illustrating an underlying theme of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The exhibits at the fair were meant to show the processes of art, education and manufacturing, not merely the results. The Cascades symbolically washed away the old, static method of exhibition in their babble and rush of flowing water.

The Cascades flowed down into the Grand Basin in the center of the image, which ran between the main exhibition buildings. The eight main exhibits included the Palaces of Education, Art, Liberal Arts, Agriculture, Horticulture, Mining, and Forestry, Manufactures, Transportation, and Anthropology (Findling 180-181). Although most of the main exhibition palaces were located below Art Hill, the giant Palace of Agriculture, covering nearly 24 acres, as well as the Horticulture and Forestry Palaces, were located to the west of Forest Park, and are shown in the far right of the bird's-eye view (Findling 180).

The main palaces separated the state's pavilions from the international pavilions and the facilities that housed the Olympic Games, which were sparsely attended (Findling 184). The Plateau of States, containing most of the state buildings, rose to the southeast in Forest Park. The U.S. Government Pavilion was to the north of them. Many foreign nations erected structures based on indigenous historical buildings, the majority of which were located on the Washington University Campus (Findling 180). Behind the main exhibition buildings were the amusements, including a 13-acre reproduction of the city of Jerusalem, as well as a large Philippine Reservation with twelve-hundred residents (Mattie 120)

The amusement concession area, the Pike, extended 1 ?? miles from the main fair entrance west to the end of Forest Park, turning sharply at Skinker road and continuing west (Findling 181). Containing 540 amusements and concessions, the Pike reflected the imperial vision of the exposition's promoters, who intended to shape the way in which the fairgoers viewed the world (Findling 183). The Pike featured the Cliff Dwellers, Zuni and Moki Indians who had "never been shown before." It also included Mysterious Asia with camel rides along winding streets, and the Geisha Girls entertaining visitors to Fair Japan. It was said that to see the Pike was to see the entire world. The Pike remained open in the evening when exhibit palaces had closed. Most Pike attractions ranged from ten to fifty cents, but some visitors could not afford to pay these prices (Findling 184).

The giant Ferris wheel, located in the amusement area, carried visitors over 260 feet in the air for the best panorama of the fairgrounds. People rented cars on the wheel and partied on board, experiencing a unique atmosphere created by evening lights in and around buildings, and under arches and cascades, all the while marveling at the technology of the large wheel. A stunt woman even made two revolutions standing on top of a car on the observation wheel (Findling 184).

The buildings, designed to look imposing and permanent, were made to be temporary, with the exception of the Palace of Fine Arts. This partially explains why very little steel was used in the construction of the buildings. Although it presented a fire hazard, wood was the material of choice for the great exhibit palaces. The use of wood made the application of staff, lightweight material molded onto the buildings, much easier to apply (Findling, 180). Staff was versatile, and could be painted any color. The staff was painted an ivory color throughout the fair, dubbing the exposition the "Ivory City" (Mattie, 120).