Manufactures Building

Manufactures Building

By Aaron Zephir

This text is freely available for the purpose of academic teaching and research provided the text is distributed with the header information provided.

Download EssayEssay on the Manufactures Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois created as a final assignment in World's Fairs: Social and Architectural History , HONR 219F, Spring 2001

Titles of texts, foreign words, and emphasized text have been encoded

Keywords:

- World's Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.)

- Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. World's Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.)

- Exhibition buildings -- Design and construction

- Essay

- 1801-1900

- North America

- United States

- Illinois

- Chicago

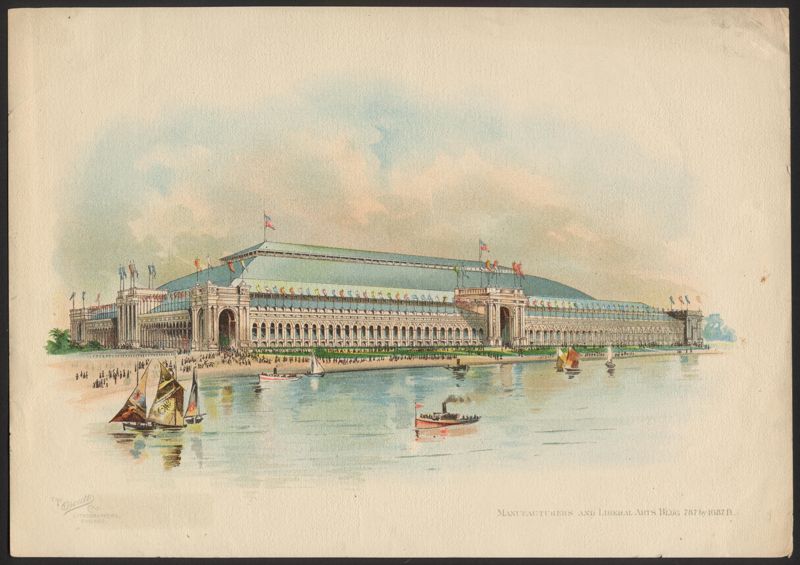

This 11 by 7 inch color lithograph seen here depicts the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building at the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. As the main exhibit space of the fair, it was the largest building ever constructed at the time and the most visited site at the exposition. The general scheme for the building was laid out during the early planning stages of the Chicago fair. It was to be located facing Lake Michigan on its long axis and the east end of the Court of Honor, where the other main buildings were grouped, on its short axis. Architect John Wellborn Root, partner of fair director Daniel Burnham, devised the basic function for the building. Because Root died early in the planning stages, the program was radically altered by his successor Charles Atwood. The latter's idea for a clear span surrounded by galleries prevailed, as fair organizers were intent to surpass that of the famous Galerie des Machines at the Paris exposition of 1889. New York architect George B. Post (1837-1913) was chosen to design the Manufactures building from a group of mostly eastern architects selected for the major fair buildings, including Richard Morris Hunt and McKim, Mead and White. His experience in large classically detailed New York buildings such as the Produce Exchange (1881-84) and the Havemeyer Building (1891-93), both demolished, made him a good candidate to uphold the White City ideal of the fair, emphasizing classical canons of composition and ornamentation. His expertise in the use of iron and steel, as in the large interior light court of the Produce Exchange, would come in handy if the Manufactures Building was to succeed in its "clear-span rivalry" with the Galerie des Machines (Hoffmann).

Post succeeded in both aesthetic and technical challenges. Not only the largest building at the fair, the Manufactures Building was one of its greatest architectural assets. It measured 1,687 by 787 feet, had an exhibit space of 44 acres, and a central hall spanning 370 feet and rising 211 feet. The great steel arch trusses were certainly the building's most remarkable feature, left exposed and filled in with glass to form a greenhouse-like ceiling that allowed light to pour in. Surrounding the central space were galleries with additional exhibit space that looked down into the great hall. The exterior was no less impressive. Constructed of the same reinforced plaster as most of the other buildings at the fair, the Manufactures Building featured a severely classical fa??ade. Its uniform Corinthian arcade ran in a continuous sweep for the entire length of the building, interrupted only by the triumphal arch motifs of the central and end entrance pavilions. The building was the only one at the fair to feature such an open arcade, and as such was very popular among visitors seeking a place to rest in the shade and enjoy the view of Lake Michigan.

The appeal of the Manufactures Building was based not only on its architectural merits, but also on the wealth of exhibits inside. Since the building was essentially one large room, interior space had to be parceled out to each nation, leaving room for a wide aisle in each direction. At the intersection of these aisles, in the center of the building, stood a 135-foot alabaster clock tower from the American Self-Winding Clock Company, with arches at the base that allowed circulation underneath. This clock acted as a focus amid the jumble of exhibits. From atop its tower, one could gaze down at the exhibits of the four greatest nations: the United States in the northeast, Germany in the northwest, Great Britain in the southwest, and France in the southeast. Behind lay all the other nations of the world among a mind-boggling array of artifacts. Displays of Belgian lace, Austrian armor, German military armaments, and Italian marbles and sculptures attracted particular attention. The French exhibit was exceptionally beautiful, marked by a huge hemispherical niche containing a statue of the Republic. The British exhibits were also noteworthy, especially the vast collections of ceramics and porcelain from such famous manufacturers as Crown Lambeth and Wedgwood. But one of the most popular and eye-catching displays was that of the Tiffany Company in the United States section. Its colossal gold Doric column topped by a glass globe and golden Eagle was one of the most conspicuous landmarks inside the building. The diamond exhibits alone numbered over 10,000 pieces, including the gray canary diamond, Tiffany's greatest showpiece set on top of a rotating velvet pyramid.

The Manufactures Building was without a doubt one of the most critically praised of all the fair buildings. Its sheer size, proliferation of exhibits, and stately fa ade received almost universal acclaim. American world's fair correspondent Trumbull White compared the role of the Manufactures Building at the Columbian Exposition to that of the Eiffel Tower at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, as both were "the principal point of attack for every sightseer" (95). American Architect and Building News called it "the most successful fair building of the whole group and, withal, extremely interesting and abundantly architectural in its treatment" (85). It is difficult to find negative criticism of this building other than that of the progressive Chicago architects who despised everything classical and historicizing about the fair. However, Sullivan and his followers were a minority; most critics thought the building a complete success. Even so, it was always meant to be temporary, and it was torn down the year after the fair. The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building served its purpose well, and when that purpose was complete, its life was also.